Designing organisations that really work

The very fact that you first pull together organization charts to make decisions on how a team is structured is flawed. Explore what it takes to design highly effective organizations.

Today, global scale makes businesses grow fast. Disruptive business models and platformization translate to 10x growth within months for both start-ups just launching or an established organization focusing on a new idea. Over the last ten years, there has been a lot of research on how businesses adapt to competition, scale and driving innovation in the new environment. The same statement would however not be true and parallel to how businesses build organizations and structure that scales. Even today, cost and ownership remain primary drivers to how organizations are structured.

Like intensity, organizational design is also a key decision that sets direction and culture. Good structural design is based on the “how” work flows through different points in your organization.

The very fact that you first pull together organization charts to make decisions on how a team is structured is flawed.

Design that centers on cost and ownership come with their own fallacies and binds your organization with constraints including higher cost of collaboration, increased time to make decisions and a workplace that your top talent does not enjoy working in.

I’ve worked with teams where we reference this environment as a “partnership standstill”. A situation where the effort of collaboration and debate is significantly higher than the cost of just doing it yourself. This pushes the culture to avoid collaboration because there is just so much effort required in doing it. Imagine having to jump through multiple hoops to review and get started on a small idea. The cost of debating this would be so high that you would just either drop the idea or you would just do it and not tell anyone else.

Partnership Standstill = Cost of debating/collaborating > Cost of doing

Designing Right

Organizational charts represent ownership and reporting structure. It is a primary method to study who owns what and how control is exercised. It would be ineffective to use them as a singular artifact to design structure. The crucial components of design lie in how work flows from one point to the other in your organization, primarily a map of how value gets added to your product. I always start with what I call a “value map” that would generally apply to any organization. When I encounter additional information, I enrich my maps to ensure that it represents the context of the teams I work with.

Practical to-dos

“Follow the money” is a phrase used by finance professionals when auditing. If you follow transactions from the origin (where money is made) to the spend (where the made money becomes zero or even negative), you will have all insights you need on a business model, a forensic audit, etc., Similarly, you need to “follow the decision” to create your own value map of your business. Attach yourself to a business problem, analyze its point of origin and all the decisions it takes to solve them. This helps you develop insights you need for building the value map.

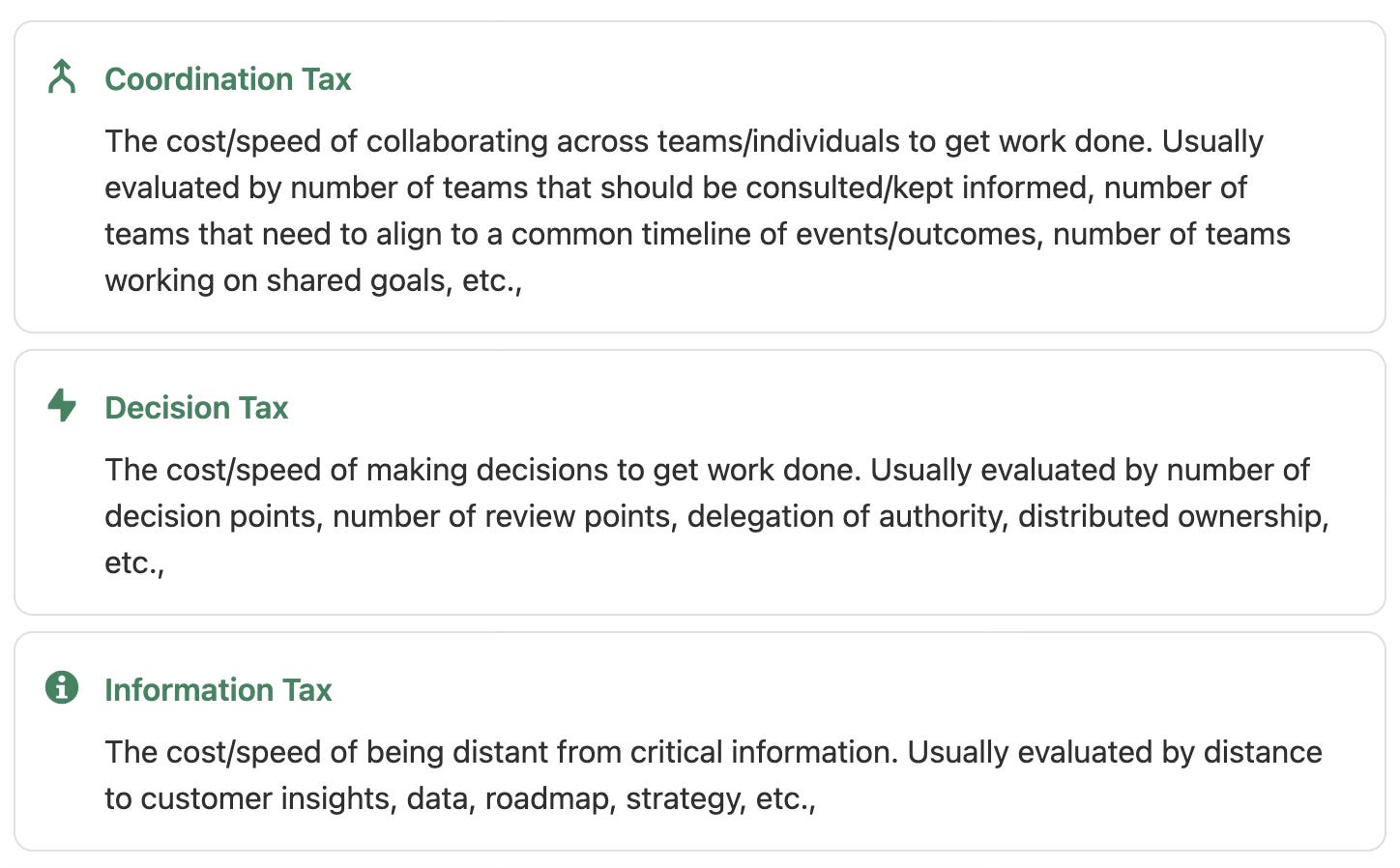

There are three elements to designing structure that enables building great teams that work well together. Good structural design aims at minimizing the cost of these elements.

Consider for a moment that you are reviewing a proposal to build a technology team in another country because talent is cheaper (a cost based decision to structure). To illustrate how these elements play out, I’ll use the default value map I have and add a second location. The moment you set up a team in another country, observe the three design elements and the relative complexity to getting work done significantly going up.

In this illustration, when the tech team is started in another country, the team needs to start coordinating with multiple partners including the parent tech team in the home country, the product team, the operations team and the support team. This increases the coordination tax for all these teams. And imagine a reality of the second country being in a time zone that’s 12 hours away! The teams slow down for being inclusive with time zones and instances for “thread delays” (where team A would have to wait for team B to deliver/respond) start to crop up. It also leaves your top talent with a frustration of not being able to get things done.

Similarly, the number of decision points in tech direction and architecture will increase, with expertise spread across these countries. This increases the touchpoints for the product team with the need to enable tech decision making. This would mean that every idea jumps through additional number of hoops before it sees light. Your team would feel as if they have to pocket a follow-on for every coin and not only for the critical red coin. In a long run, it will result in slower go-to-market and creating a workplace culture that may not be attractive.

Distance to critical information increases for the new team. Customer and market insights shape work in the information age. If the flow of information between these teams is slow, then the second team is probably working with information of decreasing relevance. This stifles their ability to design and deliver products.

Practical to-dos

Build a value map of your team. Attach a shirt-size (XS,S,M,L,XL) to the amount of coordination tax, decision tax and information tax that exists between teams and create an action plan.

If you are evaluating a structural change, build a value map and discuss with your teams. As you manage through the change, set expectations with teams where the costs of the elements will be high. Set up a task force and timeline for building an action plan.

In my exploration, I’ve used a few tools to that help managing the fallout of inefficient structural design.

Mitigating Coordination Tax

Add Roles that absorb coordination tax: Investment in roles that bring delivery predictability and alignment like project management, program management, launch management help reduce the coordination burden from the team. If you have shirt sized the coordination tax in your value creation map, you know exactly where to invest.

Self sufficient teams: Creating task based teams with a representation of all skillsets required to solve the problem help reduce the coordination required. This team comes together delivers on a particular theme and then disbands.

Mitigating Decision Tax

Executive sponsors: If there are multiple decision makers, delegate to an executive sponsor who will make all decisions related to a certain initiative. Your value creation map will help you identifying investment areas where you need an executive sponsor.

Leadership Coverage: Have a ratio based tenet to empower decision making. For instance, if the decision does not impact 2 or more teams, a leader at a “x” level can make the decision. As you focus on designing the organization, you should ensure that this “x” level leadership is available at ease across any two teams.

Mitigating Information Tax

Roles focused on information availability: Invest in a team that focuses on information availability across all your teams. This typically is a business intelligence/analytics capable teams that produces digestible insights on customers. Your value creation maps will help identify investment areas.

Democratize information: Publish critical information at scale to be available at scale. I once worked with a team that had an internal page accessible to everyone in their organization on what appeals most to their customers in certain demographics. I’ve also seen product grids that communicate critical features that retain customers (what most of their customers use most of their time) vs critical features that detractors don’t have alternatives for (what customers who least used their products most of their time). Another innovative practice making crash data for products be available to everyone in the team.

Great leaders are careful architects of their structure. The three elements of structural design directly impact flow of work, information and innovation. At senior leadership, the ability to carefully make structural decision choices is the key lever to success. If you are wondering why this article does not have references to how people and leaders are mapped to a structure, that’s the final part that ideally should not affect the design. Your path to value creation should determine structure and you find leaders to manage value creation and not manage value creation basis leaders you have.

Have a point of view? Do you have more tools that you use to manage these elements? Let’s talk!